If you are asked what have been the greatest achievements of your life so far, you can be excused for thinking of things you have done in your adult years – when you have more consciously taken your life in hand out of your own free will and initiative. As we look towards Christmas and the New Year, thinking about new birth and new light, I like to think of a completely different time of life, one we usually don’t even remember, yet its achievements affect us profoundly for life: the young child from birth to approximately 3 years of age.

The first year and walking

The first absolutely amazing feat of the first year of life is birth itself. In one final act, the world of the newborn has been turned inside out. Protected and nurtured before in the womb of the mother, the child is thrust into a new world exposed to the elements, vulnerable and unprotected. As parents we then need to take on the nurturing and protection much more consciously.

This event is a wonder in itself, and much could be written on what happens at birth that gives a picture for life, but here I focus on another feat of the first year: the drive for uprightness and walking.

There are interesting expressions that someone ‘has an upright character’, or someone should ‘stand on their own two feet’. Little do we think of their origins as being in the first year. The upright stature is one of the first outer developmental features that distinguish us as human beings. To have an upright character implies that we are grasping a higher quality of what it means to be human. To stand on your own two feet implies taking your next steps on your own, learning to do something yourself.

The drive for uprightness and walking happens in many stages, quite early distinguishing itself from the development of other animals. Consider the foal. A few hours after birth it is already struggling to its feet. The animal’s inborn reflexes bring this about. The human infant is born with some of these reflexes – for example, an automatic stepping motion at a couple months if his feet touch a surface – but he has to let go of such reflexes in order to learn through voluntary movements. One of the first gestures towards uprightness is the determined raising of the head. By 4–6 months the infant is pushing up with both arms to try to raise his upper body. By around 9–10 months he can sit upright; in another month or two he is using his hands to pull himself up and hold himself in a standing position. The temptation is there for some parents at this stage to provide aids such as walkers. Don’t do this: it’s important for the child to learn to walk on his own initiative and by his own efforts. And then…

Those first tentative steps! This is one of those moments that stands out and fills onlookers with wonder, amazement and joy. As parent, you watch, eyes wide open, mouth dropping open in astonishment, as you see your little one letting go, looking at you with eyes also wide open and sparkling, as if to say, “Here goes! Look – I can do it!“ Whoops, a fall – try again, and again. So your child learns, with incredible persistence, every child at his or her own pace and pattern, no two the same.

And so uprightness is achieved. It is a spark of the human spirit that can give us strength throughout life: the courage to be upright and take the next steps.

The second year and the mother tongue

Another momentous step happens in the second year. This time it is a more inward one: learning to talk and the acquisition of the mother tongue. The process is quite extraordinary.

Up to between about 6 and 12 months, all children are capable of learning any world language equally. At 1 year your baby will most likely be experimenting emphatically with a few one-syllable ‘words’: “Mmahh!” “Dahh!” ”Bahh!“ – relieved if you finally realise the meaning!

After this point, the palate and importantly the brain start forming themselves according to the mother tongue, with all the unique sounds, accents, gestures. It is in these first years that language plays an active part in helping create and map the neural pathways in the brain – an intricate and essential part of the foundation for thinking. And the breadth of language experienced at this time influences children for life, including how well they do in later years at school. In conjunction with studies about the lower academic performance of children who have grown up in poverty, researchers came to the startling finding that this was often related to less conversation and play and more screen time at home. The toddler cannot acquire new vocabulary from tapes, screens or other technology as older children and adults can – and in the under-3s these were shown to actually detract from language learning. This was initially a surprise. The realisation was that with tapes or screens the experience of a real person was missing.

Language learning in this early period is triadic: a triangle with the child, you, and the world around. This is why pushchairs and slings with the young child facing you and not outwards are better for language learning. The interaction with a closely connected person is vital.

The child looks at you, and then at the bird. You point. “Look, a bird! Oh, it’s flying away!” The child looks back at you, excited, exclaiming, “Bird… fly!” You sing a song about a bird.

Thus we discover again with new insight what our grandparents instinctively knew: for learning to speak, the young child needs us to be present, in the here and now, talking, singing songs, telling nursery rhymes and stories – sharing our joys and our love.

The third year and thinking

We hear ever again the question of whether nature or nurture is the most important influence in childhood. Many people say the answer is both, equally, and a new cohort now speak of epigenetics, with the discovery that genes can be turned off and on by the environment.

And that’s where many stop – nature and nurture combined sums it all up. Yet something important is missing. Something that modern materialistic society has the hardest time getting its head around, which in turn is related to the third year: the wonder and mystery of consciousness and the development of self-consciousness. This is connected to the development of thinking. What is happening?

In the first year of life the child is not consciously thinking about how to crawl, sit up and stand – this is an instinctive intelligence that is body-bound, responding also in imitation of the uprightness of the surrounding adults.

Again, in learning the mother tongue, the 1–2-year-old is not thinking about it: the child is imitating words, relating each word directly to an object or action, not yet able to link words in sentences through reflection. Memory is related to objects and the location of something – ‘local memory’. The child may forget the hurt from a tumble on the stairs if she is now outside, but if she returns to the stairs she may suddenly start crying again. It is as if the environment were speaking and prodding the child with the thought content – and maybe it is! The child lives in the present, in oneness with the world.

Thinking makes a significant step during the third year. The language heard and imitated in the second year has been forming the brain and thinking ability; this in turn enables further differentiation in the spoken sentence structures in the third year. As with previous stages, trying to artificially insert any instruction will only harm the process. The child observes and absorbs what he needs from a loving environment where he can not only play but also watch and interact with others in everyday tasks such as washing dishes, cooking, cleaning. The logical order inherent in these activities takes on new significance for the child’s thinking at this stage. It is called ‘embodied cognition’, whereby thinking is formed through real-life experience. Aspects of this continue through childhood, some saying it forms a basis for ‘common sense’ later.

The final crescendo, a seed for life

There comes a defining moment in the child’s development, towards 3 years of age. Something very new enters, a new experience of self. It is at the same time one of separation: I am here, you are there – the child can now say ‘I’. The use of this simple word is a sign of a momentous inner step in the incarnation of the child. The child is no longer purely in the experience of the present; memory takes on a more conscious character, strengthened by rhythms and repetitions. It is consequently the point we can remember back to as an adult.

Think back to when you held a baby in your arms. The smiling, the crying, the eyes looking up, at first as if to another world, but eventually able to focus on you. Hand on heart, who can honestly say, “There lies simply a bunch of molecules and genes”? That is the logic behind the nature/nurture argument. Another ‘presence’ is there. Another being. Another consciousness.

Step by step, that ‘presence’, the inner spark of spirit, enters into the child, a crescendo through the first three years, its completion creating a living archetype: will-filled uprightness, the inner life of language, the development of thinking and self-consciousness. All are hallmarks of what makes us human. They are gifts of the spirit, our own true self. Even if we don’t remember them, the three qualities are there as a treasure and seed for us to work with for the whole of life.

____

Richard Brinton trained and worked as a Steiner Waldorf teacher, and was later Principal of Hawkwood College, UK. A father of four children, he now lives and writes in Stroud with his wife, Maia, who is also a teacher. He is a contributor to My Camino Walk #2.

Find out more: A Guide to Child Health by Michaela Glöckler and Wolfgang Goebel, published by Floris Books

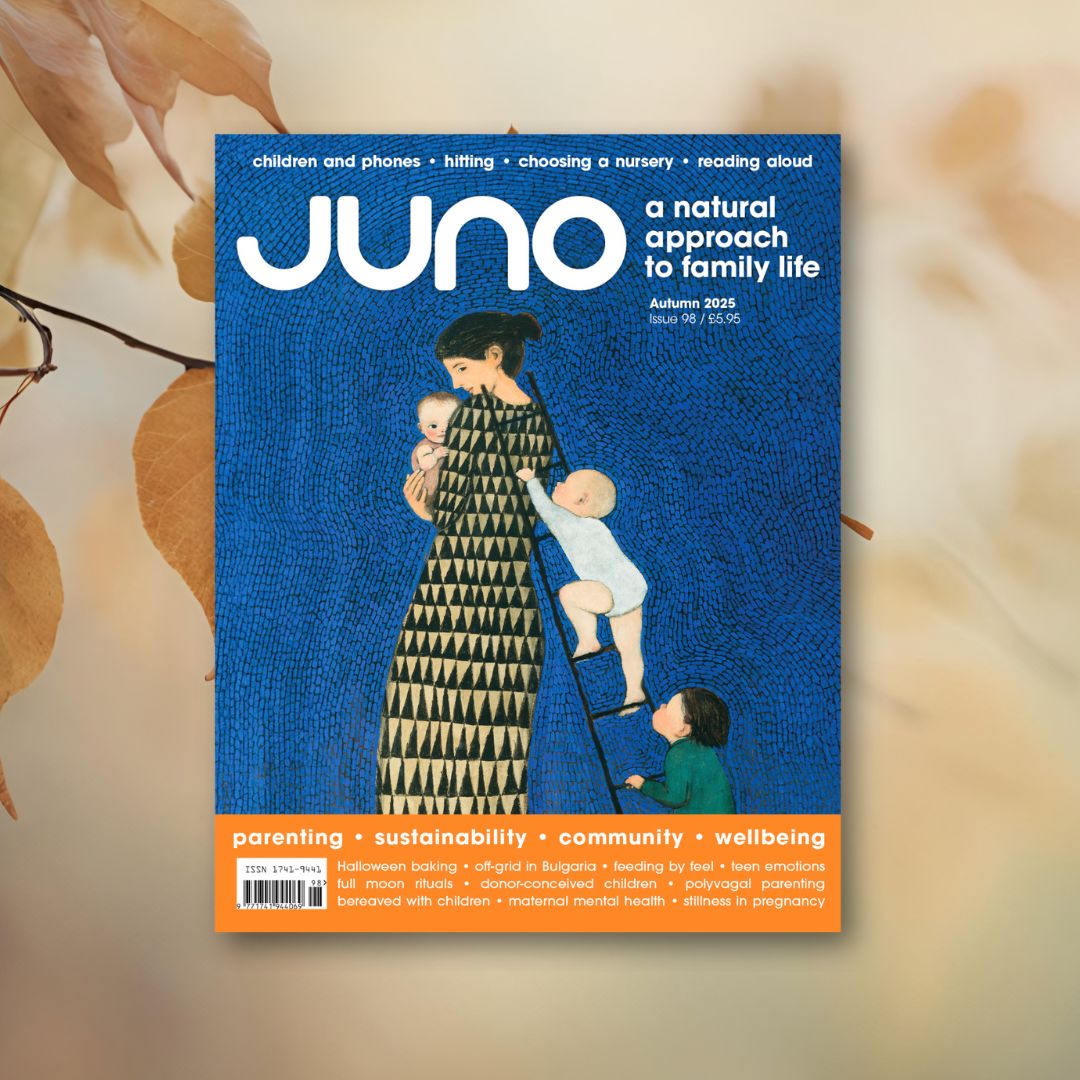

Photo: Людмила Ульянова

____

First published in Issue 58 of JUNO. Accurate at the time this issue went to print.